Marcel was 11 years old when he was on holiday with his family. Curious about his body and that of others, he followed an older man into the forest. What started as an exiting experiment, got rapidly out of hand. In minutes he lost control. His personal boundaries were transgressed in ways he wasn’t able to understand. This was no longer fun and exiting. It was invasive and abusive.

Marcel struggled to get loose. He was lucky to get away. In blind panic he ran back to his family. Back to safety, back to his mother. However, every step closer to home made him regret the decision he made. His parents did caution him not to go with strangers… fear transformed into guilt with every step. He ended up saying nothing to his parents, and chose to deal with this secret on his own.

Boy running in the forest – screen capture from Methode Naturelle

These few minutes have made a tremendous impact on Marcel’s life. Exploring his sexuality was a not something he took lightly. Setting his boundaries in intimate relationships was extraordinary hard. His dreams were filled with moments like the one I just described. It became harder and harder to lie to his family about his feelings. An although he thought that once you start a lie, you stick with it, he slowly discovered that lies only grow bigger over time.

10 years ago, Marcel and I became friends. I was the first person he trusted with his secret. We found a psychologist and he worked for years to put his feelings and fears in perspective. And I felt as if I could not help.

The Lyst Summit 2014 – photo by Gemma Thompson

The Lyst summit

Gladly, two years ago a particular event presented itself with an opportunity to support Marcel as a friend. The Lyst Summit in Denmark, organized by Patrick Jarnfelt and Andrea Hasselager, explored how developers could integrate love, sex and romance in game design. I was invited to speak on behalf of our foundation: Games [4Diversity] about the way LGBTQ perspectives could incite new and innovative gameplay.

At that moment I was working on a project called Games [4Therapy]. We explored the design process for therapeutic games. Our targeted audience was clients with externalizing problems. I did not get it… I did not understand what it felt like to be so quickly angered as our clients were. Nor was I able to phatom what it meant to (always) blame someone else for things that went wrong.

Because I couldn’t relate to my targeted audience’s feelings, I could not come up with a good design practice. Struggling with this situation, I talked to Marcel. He said, ‘It’s kind of funny that you don’t understand them, but you do understand me’. That’s when it hit me: why not make a game for Marcel?

I asked Marcel to accompany me to Denmark and enroll in the gamejam of the aforementioned Lyst Summit. We decided to make a therapeutic game for sexually abused children. This meant that we needed a therapeutic expert, a designer and developer that were accustomed to creating serious games. We invited Frank Lips, a close friend of mine and psychologist in the field of sexual child abuse. He was thrilled to see what ‘my game world’ could do for his clients. I also asked Tim Pelgrim and Paul Bierhaus from the company YipYip to join the effort. I knew both of them from my time at Ranj Serious Games, and knew that they would treat the subject with care and (more importantly) without any preconceptions.

Tim Pelgrim, Menno Deen and Paul Bierhaus during the Lyst Summit GameJam

We traveled to Copenhagen and joined the Lyst Summit, which was held on a boat in the harbor of Denmark’s capital. The summit turned out to be and inspiring event with great speakers like Ernest W. Adams and Richard Lemarchand.

On Friday eve we started to conceptualize the game. This resulted in futile efforts to connect Marcel’s feelings, which were rather diffuse, complex and intertwined to clear and strict game mechanics.

Intense conversations – getting to the heart of it

However, after four hours of brainstorming, prototyping and discussions Marcel stood up. He said, wait: I think I need to tell the full story for you to really understand what I went trough. He started, and talked for two hours straight. We listened, waited, and let Marcel spell out every insecurity, anger and joyful moment of those few minutes, more than 18 years back. After his monologue, Marcel leaned back, tired. We did not have any questions, we did not need any extra explanation. We understood. And I understood better than before, what it meant if your boundaries are transgressed on such an intimate level.

It turned out that after Marcel’s story, we all had a moment in our life where our boundaries were transgressed on an intimate level. Those moments were hard, painful and sometimes they made us angry. Our stories were related to those of Marcel, with the exception that we were adults. Still, this connection made it easier to relate to Marcel’s feelings. Everyone shared his story, and suddenly the gamejam became one of the most intimate and sharing events that I have ever experienced.

While opening up to one another, we found two commonalities in our experiences. 1. Setting boundaries is hard and 2 talking about these experiences was even harder. We were often searching for words to describe the feelings, and the activities from which these feelings emerged. Finding the right words for body parts that fitted the tone of the discussion was hard. We were troubled by using terminology such as penis, dick or phallus to describe particular body parts? More difficult to explain were the sexual activities we performed. It was hard to be explicit and still describe the ambiguity of our feelings during the intimate situations.

It became clear, that we needed to present children (and ourselves) with a different language. This language should fit the ambiguity of sexual and intimate feelings. Preferably, the language was non-verbal, discarding the need to search for words. What’s more, we thought it extremely important that we educated children to say no, to set their own boundaries.

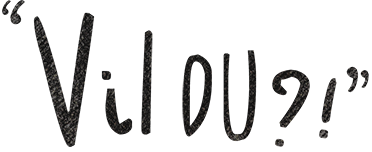

VilDu?! – Two character on two iPads

VilDu?!

This resulted in a game in which children could explore intimate or sexual relationship with someone in non-verbal ways and with a focus on boundary setting. The game resembles typical ‘dress-up games’. Two characters are positioned on an iPad, Players can perform various sexual actions to the other character, by dragging various icons over the character’s body. Both player hold an iPad, and can see the movement of the other player on their screen. In the center of the screen a prominent button says: TIME OUT!. When hit, the game freezes. In order to continue, the person who hit TIME OUT!, should agree to continue.

It’s a simple game, or maybe better, a playful tool that offers children the opportunity to express their feelings and tell their story in a non-verbal way. It resembles the reallife dolls that are sometimes used in therapy sessions, with a big exception: the focus on setting boundaries.

After the gamejam we entered the game to an innovation competition by the KF Heinfonds. We won a sum of money to further develop the game. This award was an incentive for mental health institute the Rading to invest double the money and invest it in the actual development of VilDu?! Now, two years after the jamsession, the game is almost finished. As we speak, the game is implemented in therapy session of de Rading.

We think that the game may lower the boundaries to talk about sexual abuse or rape, and maybe offer a safe space to explore intimate relationships. As said, we are still implementing the game in therapy sessions, but I am rather proud that Marcel’s story can help children to open-up and tell their story.

Early sketch of VilDu?!

VilDu?! is now being implemented in therapy sessions. We are working on a training module to teach other therapist how to use the game in sessions. Furthermore we are actively reaching out to other parties in mental health care, forensic and education. So far the game is used in a couple of session.

How VilDu?! helps children

Most exemplary is the case of an 8 years old, mentally challenged girl. She was sexually abused by her neighbour and did not dare / was not able to tell the full story. When prompted, whether she had told the full story, she clearly stated that ‘not everything was said’.

The therapist introduced her in the third session to VilDu?!. They played around in the game for a minute or two. She thought it was tremendously funny to undress the older man, stating: ‘Ha! Now are you naked!’. After playing around with the game, the therapist returned to his initial question: ‘what happened, what haven’t you told us yet?’. She piped down, stared to towards the ground and said nothing.

‘Could you maybe show it… with the tablet?’ the therapist suggested. The girl nodded. Dressed down the older man, selected the hand from the GUI and said: ‘like this, with his fist…’ She moved the hand back and forward, suggesting that the man was masturbating.

The eight years old girl, did not know how to explain what happend. Both her understanding and vocabulary fell short. She literally did not have to words to describe masturbation. Now she could show it instead.

Traditionally, the therapist works on building trust between him and the client. Then he needs to develop shared vocabulary about sexual acts and intimacy. With VilDu?! he accomplished in 5 minutes what would normally take three weeks.

What we learned

The development of VilDu? presented us with various insights in the development of therapeutic games. One of the most important to us is to focus on something small. Designers could search for something easy to relate to, instead of problematizing the disorder as something difficult and exuberant.

In hindsight we learned 3 important lessons from our design experience:

- Subtilizing the problem: Identify (with) one aspect you can relate to

- Create a non-normative play space

- Design for ambiguity, which can stimulate conversation

Subtilizing the problem

With subtilizing the problem, I mean that, even though sexual abuse and rape may feel as a it does not concern you, this does not mean that this is the case. Everyone who has been in an intimidate relationship, had his or her boundaries transgressed in smaller or bigger ways. Tapping into those experiences will help to design something that connects to this experience. By subtilizing the problem, I mean, make the traumatic experience of someone else smaller and easier to relate to. This helps you to understand the experience. More interestingly it may enrich the design process with your personal input.

Create a non-normative play space

VilDu?! Is in it essence a non-normative game. Everything is possible, without us (as designers) making preconceptions about what is right or wrong. For example, in VilDu?! players can choose any character, from young to old, from male to female. They can engage any type of relationship in sexual or intimate play. The game does not stipulate which relationship is most ‘healthy’. Instead it suggests that every sexual relationship is ok, as long as you are able to say no. As a result, the game doesn’t demonize the players but may open up discussion about sex instead.

Design for ambiguity

Lastly, VilDu?! is a rather explicit game. You can undress characters until they are fully naked. The action-icons are based on physical parameters of the characters. Amongst others there is a vagina, a penis, a hand, a tongue, a mouth. These are rather explicit. However, the use of the icons can have various connotations. It’s not the game that explains how to interpreted play, it is the player who give meaning to interaction. A hand on an arm, could mean stroking and caressing the arm. However, it can also be used to slap or pinch someone. This ambiguity invites players to express what they are doing, helping them in small steps to verbalize what happened or what they wanted to occur.

The design of VilDu!? was a rather enriching experience. Not only for us, as designers, developer and psychologist, but it was also a valuable experience for Marcel. For him, this was the very first time to tell full story, from start to end. As a result he had to put things in chronology. This presented him with a clarity he had never seen before. Furthermore, the understanding of peers and friends helped him to slowly overcome his shame and feelings of guilt. Today, Marcel can handle his intimated relationships in ways he couldn’t before.

![KF Hein Foundation co-financed the development of VilDu?! [Paul Bierhaus, Menno Deen, Frank Lips and Tim Pelgrim]](assets/images/story-images/stimuleringsprijs.jpg)

KF Hein Foundation co-financed the development of VilDu?! [Paul Bierhaus, Menno Deen, Frank Lips and Tim Pelgrim]

I am grateful for facilitating this change and helping Marcel to put his feelings in perspective. I am proud that today, he really understands that saying no is not only ok, but saying no is the basis of a healthy intimate relationship.

Thank you.

Menno van Pelt-Deen